Why Joseph Kabila’s ambition endangers Congo

Congo’s president clings to power even as the hinterland erupts

“LET’S march on the president’s palace and drive him out,” howled the speaker, and a couple of hundred supporters, packed into a sweaty courtyard at the headquarters of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s main opposition party, yelled their agreement. Outside, a contingent of police, heavily outnumbered, waited nervously. The march never happened. It would not have got anywhere near the president, and no one, for the moment, wants to risk a repeat of the violence last September, when police opened fire on crowds and a hundred or so people died. But the economy is tanking, civil war is raging again in the centre of the country, and patience is wearing thin with Congo’s dictatorial president, Joseph Kabila, whose final term in office expired five months ago.

Mr Kabila has misruled Congo for the past 17 years, after he took over from his father, who was shot by a bodyguard. The past few months have been particularly desperate. Congo depends on copper and cobalt, and to a lesser extent diamonds, for hard currency. Nearly all manufactured goods are imported. Despite a mighty river and abundant rainfall, its broken-down infrastructure means it imports much of its food, too. At the Momo supermarket in the capital, Kinshasa, a ramshackle city of 12m people, you will find tin pans from Pakistan, toilet paper from Turkey, sandals from Thailand and glass tumblers from Brazil: but virtually nothing from Congo itself apart from some of the chicken and beer.

Latest updates

The world copper price halved between 2011 and 2016. Cobalt is still well down, too, after a crash in 2008. The two commodities have recovered a bit this year, but this has not prevented the collapse of the Congolese franc, as the central bank printed more money in response to falling receipts: it has lost 50% of its value since November. Chantal Ngoyi, a trader at the big Victoire market, sells clothes (none of them made in Congo) out of big bundles of Western hand-me-downs she buys for $250 from importers. The bundle used to cost 1.8m francs; it now costs her 3.6m, so she has to pass the increase on to her customers. “Now no one can afford to buy from me,” she complains. John Mbala, who runs a liquor shop nearby, says demand for his imported booze has simply vanished. Even the cheap local hooch, like his eye-watering Boss Whisky, is not selling, because everyone is broke.

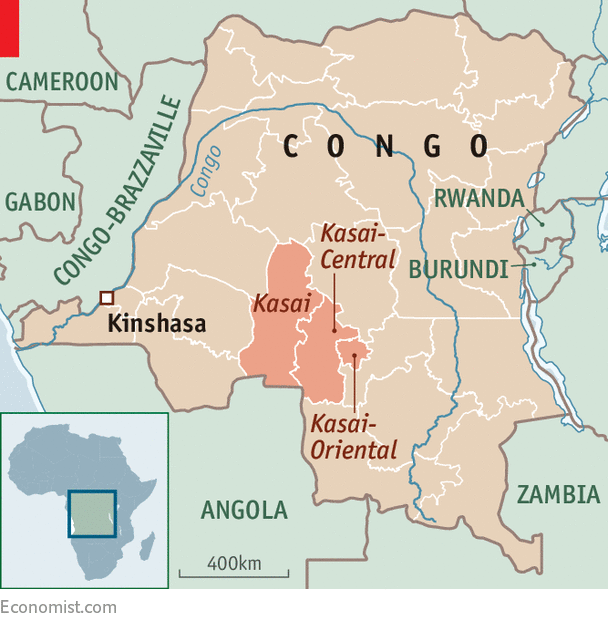

The news from central Congo is much worse, if little known outside. Back in August, in murky circumstances, a tribal chief and militia leader nicknamed Kamuina Nsapu (“Black Ant”) was killed by the security services in the province of Kasai Central after protests following the national government’s refusal to endorse him as the next “customary chief” in his area. His militia, also called Kamuina Nsapu, hit back. The government retaliated in typically heavy-handed fashion, and the violence has spread. No one knows how many have died (estimates run from 500 to 3,000 and more). The UN says that more than 1.2m people have been displaced by the fighting in the three Kasai provinces. Together with refugees from other conflicts, Congo now has more displaced people than any other country in Africa, and probably more than any country in the world bar Syria.

Two UN experts sent to investigate were murdered in March. At army headquarters in Kinshasa officers show videos of mounds of mutilated corpses and severed heads to underline the barbarity they face. Opponents accuse the army of slaughtering whole villages of Kamuina Nsapu “sympathisers”. Forty mass graves have been found by the UN so far. “This is a popular insurrection against the Kinshasa regime,” says Claudel Lubaya, a former Kasai governor. To the government, Kamuina Nsapu are simply terrorists.

The violence imperils the politics of the whole country. For Kasai is not just any region: it is a stronghold of the opposition to Mr Kabila, and the home of the veteran opposition leader Étienne Tshisekedi. Mr Tshisekedi died in February, but his son Félix has taken over his party (politics is a family business in Congo). Under the terms of a deal worked out between the government and the opposition on December 31st, the government was given a year to hold elections, with Mr Kabila agreeing that he would not run again (he is termed out under the constitution, though some of his supporters say that the constitution ought to be changed). Voter registration, a vast and complex exercise in a country as decrepit as Congo, is under way, but it cannot take place in Kasai while things there are so dangerous. But both sides agree that there cannot be an election if Kasai cannot vote.

The opposition, a collection of parties grouped together under the name Le Rassemblement, smell a rat. They accuse the government of inflaming the situation in Kasai to delay the election and give Mr Kabila longer in office. Long enough, perhaps, to organise a referendum on a change to the constitution that would allow him a third term, a trick pulled off across the river in 2015 by Congo-Brazzaville’s own veteran despot.

The opposition has other grievances, too. Under the terms of the December 31st agreement, the president was meant to appoint a new prime minister on the recommendation of Le Rassemblement. They picked their leader, Mr Tshisekedi, for that job, but instead Mr Kabila defiantly appointed a minor opposition figure, neatly dividing and weakening his enemies. “For now, we are trying to resolve this through diplomacy,” says Mr Tshisekedi, a mild-mannered man of 53 who affects his father’s somewhat incongruous flat cap for public appearances. “But when that is exhausted, we will ask our people to chase the dictator out.” Anything might happen in that sort of situation, including the return from exile of another popular opposition politician, Moïse Katumbi, mightily complicating things.

An hour’s drive outside Kinshasa, the shell of a palace testifies to the impermanence of power. Startlingly obscene graffiti adorn the walls of the salon where a ruler once entertained his guests. Weeds choke what was once an ornamental crocodile pool. Every fitting has been stolen. It is exactly 20 years since Mobutu Sese Seko, the tyrant who ruled the country he called Zaire from 1965 to 1997, was overthrown by Rwandan-backed rebels who installed Mr Kabila’s father in his place. Shortly afterwards, Congo plunged into a horrific civil war, sucking in several neighbours. The next few months will show whether the country can manage a peaceful transition of power this time or endure another lurch back towards chaos.

No comments:

Post a Comment