Burkina Faso, west Africa’s linchpin, is losing its war on terror

Attacks are intensifying, but the authorities have no idea who is behind them

The cappuccino patisserie in the centre of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso’s capital, offers freshly baked croissants and that rare delicacy in west Africa, a decent Italian coffee. Its other features are less charming: a thick security barrier and two twitchy soldiers with assault rifles guard its patrons.

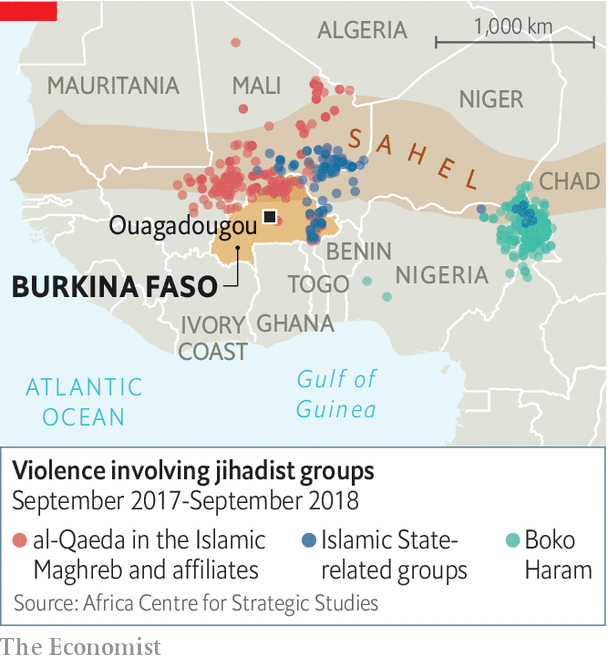

This was the place where jihadist terrorism first came calling three years ago. Jihadists attacked Cappuccino and the nearby Splendid Hotel. Thirty people were killed and dozens were injured. A conflict that had been raging next door in Mali had just jumped into a linchpin state. Burkina Faso has borders with six other west African countries; instability there could create a corridor by which jihadism might spread from the Sahel into states along the Gulf of Guinea. A long-overlooked country of 20m people is now seen as a vital battleground. And the fight is not going well.

Latest stories

Less clear is who is behind the fighting. Some attacks, such as the one on Cappuccino, have been claimed by al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, a jihadist group that operates across large parts of the Sahel. Others have been claimed by a variety of similar groups including Nusrat al-Islam, Islamic State in the Greater Sahara and Ansarour Islam. But more than 90% of the attacks remain unclaimed and unattributed.

Forensic work offers some clues. Brigadier General Oumarou Sadou, the chief of staff of Burkina Faso’s army, says that there are similarities in the home-made bombs used in the north and east, suggesting that the attacks are linked. But beyond that, General Sadou is puzzled as to the identity of the attackers, particularly in the east.

Some suspect former members of the security services loyal to Blaise Compaoré, who ruled the country for 27 years before being toppled in a people’s uprising in 2014. His fall led to the dissolution of his 1,200-strong presidential guard. Many of its members are disgruntled at having lost their privileges. There is no hard evidence of their involvement.

However, Mr Compaoré’s henchmen had long-standing links to the jihadists. The International Crisis Group, a think-tank, says that his regime cut deals with armed groups in the region, giving them support in exchange for a promise not to attack Burkina Faso. This truce unravelled in 2013, after jihadist rebels took control of the northern half of Mali. France sent in troops to push them back and Mr Compaoré was forced to deploy 1,000 soldiers to the border with Mali.

Now Burkina Faso itself needs assistance, particularly air support, says General Sadou. “Mali was asking for help before they had their crisis. No one listened,” he says. “If we do not get more help, I see the situation definitely getting a lot worse.”

Neighbours including Togo, Benin and Ghana have sent troops to their borders near Burkina Faso and have raided suspected militant outposts. But it is not clear whether Burkina Faso will get much direct support. France has already committed 4,500 troops to the region, yet they are stretched thin. The g5 Sahel, a counter-terrorism force consisting of 5,000 troops from Mali, Mauritania, Chad, Niger and Burkina Faso, which was established to deal with just this sort of threat, is struggling to get troops into the field.

Aziz Istanbul has yet to reopen since it was attacked. Its shattered windows and walls pocked by bullets offer a worrying vision of where the country may go.

No comments:

Post a Comment