AFRICA

The Big Five

Rwandan President Paul Kagame is known around the world as a leader who helped rebuild his country after the horrors of genocide.

But at home, Kagame is a brutal autocrat who tortures and assassinates his political enemies, wrote London School of Economics fellow Brian Klaas recently in the Washington Post.

Kagame apparently intends to follow in the footsteps of many other African heads of state. He recently altered the Rwandan constitution to allow him to remain in power through 2034 – a term extension for himself totaling 40 years.

“What can be done to stop African autocrats like Kagame from simply refusing to step down when they are supposed to?” asked Klaas.

Many Africans are asking the same question.

“When Will Kabila Go? Congolese Leader Long Overstays His Welcome,” read a headline earlier this month in the New York Times, referring to Democratic Republic of Congo President Joseph Kabila.

Kabila keeps coming up with reasons to delay a vote in a reelection race where he is trailing slightly in the polls, prompting fears of violent clashes between police and protesters who want him to follow the law and step down as he was supposed to do late last year.

“The president needs to go,” a motorcycle-taxi driver told the Times in Kinshasa, the capital. “By not going, he is seeking war. So we’ve decided to go to war, too.”

Africa watchers say ‘The Big Five’ elections kicking off this week will determine the future of Africa. But they add, sadly, the elections will underscore the continent’s problems, too.

Most of all, as the Financial Times noted, the elections will “tell the diverse tale of democracy in Africa.”

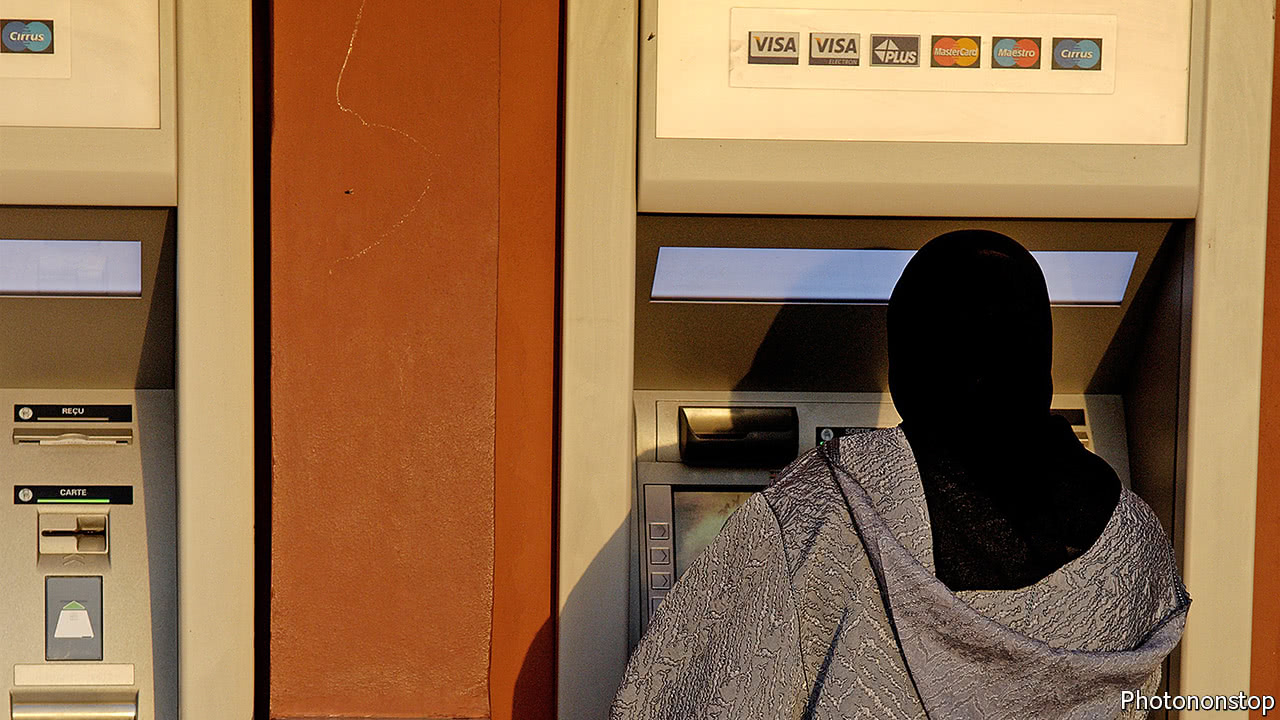

Elections are slated for Rwanda on Aug. 4. Pools in Kenya will follow four days later. And voters in Angola, Liberia and the Democratic Republic of Congo are expected to go to the polls in the next five months.

Kenya and Liberia will hold robust democratic elections, the Financial Times wrote, with Kenya hoping to avoid the violence of the last elections. Kagame will steamroll his opposition. In Angola, President José Eduardo dos Santos is stepping down after 37 years. His anointed successor, Defense Minister João Lourenço, is a shoo in as his replacement.

Voter intimidation, violence and media bias are likely to mark all of the contests, however, wrote the Daily Maverick, a South African publication. Canada’s Globe and Mail noted that those tactics are how many African leaders like Lourenço manage to remain in power for so long.

The Republic of Congo – the northern neighbor of the Democratic Republic of Congo – is a case in point.

Voters were electing a new parliament on Sunday under a new constitution enacted in 2015 that allowed President Denis Sassou Nguesso to stay in office after holding power for 33 of the past 38 years.

When Sassou Nguesso’s party won a majority in the first round of voting, which excluded a chunk of the country due to violence stemming from a rebellion, some members of the opposition decided to boycott the vote, reported Africanews.

The Congolese opposition knows what dictators don’t like to hear: it’s not the franchise if its fake.